Basque sculptor Vicente Larrea was born in Bilbao in 1934 to José Larrea Echaniz, also a sculptor, and his wife Pilar Gayarre Galbate, from the province of Navarra. The fifth of seven children, Vicente began art training early on at the family studio, at the Bilbao School of Arts & Crafts in Achuri and at the city’s Museum of Art Reproductions. His father inherited the profession from Vicente’s grandfather, Vicente Larrea Aldama, the family’s first sculptor, who in the late 19th century had opened a studio that developed into one of the most important in the city. Vicente’s grandfather had previously trained and worked as a sculptor in Paris with Rodin and other maestros. When he died in 1922, his son José took over the studio.

Vicente Larrea’s knowledge of classical models and his understanding of the resources of the sculptor’s trade, something he picked up during his early, eminently practical training, exerted a powerful influence on his work. The peculiar characteristics of a family studio also affected his approach to sculpture: for more than half a century, the Larrea workshop was responsible for many of the civil and religious sculptures still to be seen today in the province of Biscay. This remarkably solid background enabled Larrea to produce sculptures of great technical complexity. While still training, Vicente studied for his Baccalaureate at the Jesuit school in Indauchu before graduating as a technical mining and steel engineer in 1957. He completed his training with several stays at the studio of sculptor Raymond Dubois in Solesmes, France. At the local abbey Larrea frequently attended religious ceremonies with the Surrealist poet Pierre Reverdy, then retired and now buried there.

Like the work he produced during his time in the family studio, Larrea’s understanding of sculpture gradually evolved and developed as he matured. At first his output resembled the kind of sculpture done at the studio, which his father left more and more in his hands, Vicente being the only child to take an interest in sculpture. Later, Larrea was to make a clean break from what we might call traditional sculpture, orienting his work definitively towards the contemporary idiom. The break also affected the nature of the family business, which Vicente Larrea finally closed down in 1964 to pursue an independent professional career. The transformation of the sculptor’s work coincided with the appearance of avant-garde groups of Basque artists convinced of the need for an autochthonous, experimental art. They had a tough time of it getting their ideas across in the society of the day. Larrea joined Emen, the group rooted in the province of Biscay, and in 1966 took part in the exhibition Emen held jointly with another group, Gaur, from the neighbouring province of Guipúzcoa, at the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum.

In that show, Larrea presented a Crucified Christ in wood linked to the kind of religious images produced in his father’s studio, but which, at the same time, like other works of the time (Pantocrátor,Virgen) pointed to the direction he would take after his break with tradition. As befits a man who is to this day captivated by Chartres and Vezèlay, Larrea took Romanesque-inspired configurations to make sculptures whose tormented, broken forms explore and reveal, as they strengthen, the expressive force of their structural lines.

Shortly afterwards, the first non-figurative sculptures were to appear. These include 1966’s Monumento a Kirikiño, which stands by the gate to the cemetery at Mañaria, in Biscay, in homage to the writer Evaristo Bustinza Lasuen, who is buried there, and two bronze spheres from 1967, Espacios para una vida 1 and 2, soon followed by the vertical upright structure of a house on Simón Bolivar street in Bilbao, called

Shortly afterwards, the first non-figurative sculptures were to appear. These include 1966’s Monumento a Kirikiño, which stands by the gate to the cemetery at Mañaria, in Biscay, in homage to the writer Evaristo Bustinza Lasuen, who is buried there, and two bronze spheres from 1967, Espacios para una vida 1 and 2, soon followed by the vertical upright structure of a house on Simón Bolivar street in Bilbao, called  Cadena de ácidos, also from 1967, and Cepa 1 and 2, from the same year, in polychrome wood, another horizontal, circular development in bronze, entitled Bóvedas, from 1968, a circular structure now in the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum collection called Formas concéntricas 1(1968), a similar development from 1969 on the large scale sited in the Begoña district of Bilbao, Formas concéntricas 2, Formas concéntricas 3, a 1969 spherical vault´s development (Museum from provinces Bellaterra) and Bóvedas en cadena (1970). These and other works are closely related to the abstract geometric art so popular in Europe after World War 2, and to its Constructivist and neo-Plastic precedents.

Cadena de ácidos, also from 1967, and Cepa 1 and 2, from the same year, in polychrome wood, another horizontal, circular development in bronze, entitled Bóvedas, from 1968, a circular structure now in the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum collection called Formas concéntricas 1(1968), a similar development from 1969 on the large scale sited in the Begoña district of Bilbao, Formas concéntricas 2, Formas concéntricas 3, a 1969 spherical vault´s development (Museum from provinces Bellaterra) and Bóvedas en cadena (1970). These and other works are closely related to the abstract geometric art so popular in Europe after World War 2, and to its Constructivist and neo-Plastic precedents.

All the sculptures from those years, except the public works, were included in Larrea’s first one-man showing at the Galería Grises in Bilbao in 1968. In the following years, however, these heavily geometric, dynamically structured works that provided such an aggressive challenge to the surrounding space underwent a transformation towards more complex arrangements. His next one-man exhibition at the Galería Illescas in 1970 included a work marked by two contradictory developments: the geometric structures of parallelepipeds or superimposed planes similar to his earlier production and some freer, more protean, even Baroque organic elements, some times independent, others found in a particular sculpture, where they are imprisoned by the geometric structure.

With works from this 1969 series bearing the generic title of Cárceles, in which the two elements coexist, and the one entitled

With works from this 1969 series bearing the generic title of Cárceles, in which the two elements coexist, and the one entitled  Farraluque, a tribute to the character from José Lezama Lima’s seminal novel Paradiso, published in 1966 and soon a benchmark for the new style of novel then coming out of Latin America, Larrea was also included in the exhibition of Basque Art held in 1970 at Mexico’s Centre for the Fine Art. Larrea visited Mexico for the exhibition accompanied by the curator, José Luis Merino González, and fellow sculptors Nestor Basterretxea and Remigio Mendiburu, who also had works on display there. In the 1970-71 academic year, Larrea taught sculpture at the newly inaugurated Bilbao School of Fine Arts. However, he gave up the post because he disagreed with the teaching system, which he felt was totally inadequate for stimulating students’ creativity. This was a crucial time for Larrea’s work.

Farraluque, a tribute to the character from José Lezama Lima’s seminal novel Paradiso, published in 1966 and soon a benchmark for the new style of novel then coming out of Latin America, Larrea was also included in the exhibition of Basque Art held in 1970 at Mexico’s Centre for the Fine Art. Larrea visited Mexico for the exhibition accompanied by the curator, José Luis Merino González, and fellow sculptors Nestor Basterretxea and Remigio Mendiburu, who also had works on display there. In the 1970-71 academic year, Larrea taught sculpture at the newly inaugurated Bilbao School of Fine Arts. However, he gave up the post because he disagreed with the teaching system, which he felt was totally inadequate for stimulating students’ creativity. This was a crucial time for Larrea’s work.

A sculptural component consisting of organic sheet or plate, as yet developed in discontinuous fragments, and which had begun to appear in his work increasingly clearly described in small bronze sculptures, and in the interiors of the Cárceles series, now came into its own as the sole element of a great iron sculpture called Samotracia, dating from 1970-71. Exhibited first at the Basque Art Show in Baracaldo in 1971, the work was subsequently seen at the International Art Encounters in Pamplona in 1972. Today it stands opposite Baracaldo Town Hall and remains one of the sculptor’s masterpieces.

A sculptural component consisting of organic sheet or plate, as yet developed in discontinuous fragments, and which had begun to appear in his work increasingly clearly described in small bronze sculptures, and in the interiors of the Cárceles series, now came into its own as the sole element of a great iron sculpture called Samotracia, dating from 1970-71. Exhibited first at the Basque Art Show in Baracaldo in 1971, the work was subsequently seen at the International Art Encounters in Pamplona in 1972. Today it stands opposite Baracaldo Town Hall and remains one of the sculptor’s masterpieces.

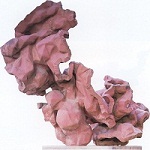

Two other iron sculptures from 1971, Caracolillo and Maia, are both on the horizontal plane and in fact very similar to each other, despite the difference in size. The larger of the two, Maia, is now in the Park of the Ciudadela, or Citadel, in Pamplona. These two were to be the last works where the sculpture was formed by discontinuous, superimposed elements. Apart from that, though, the basic arrangement featured in the following phase of Larrea’s work was already in place there: the body of the sculpture features a continuous plate or sheet of varying thickness, plant-like or embryonic in appearance and with infinite potential for diversification and development, and whose corporeity or expressivity is hugely enhanced by the mass of the actual plate, the dark hollows it encloses, and the contour of the edges or lips. Larrea’s sculptures were now always complex and dynamic, almost tumour-like in growth, never far from the opulence of the historic Baroque and with links to similar movements, whether contemporary or not. The increasingly frequent use of muscular and sexual forms also imbued his work with an explicit eroticism.

Two other iron sculptures from 1971, Caracolillo and Maia, are both on the horizontal plane and in fact very similar to each other, despite the difference in size. The larger of the two, Maia, is now in the Park of the Ciudadela, or Citadel, in Pamplona. These two were to be the last works where the sculpture was formed by discontinuous, superimposed elements. Apart from that, though, the basic arrangement featured in the following phase of Larrea’s work was already in place there: the body of the sculpture features a continuous plate or sheet of varying thickness, plant-like or embryonic in appearance and with infinite potential for diversification and development, and whose corporeity or expressivity is hugely enhanced by the mass of the actual plate, the dark hollows it encloses, and the contour of the edges or lips. Larrea’s sculptures were now always complex and dynamic, almost tumour-like in growth, never far from the opulence of the historic Baroque and with links to similar movements, whether contemporary or not. The increasingly frequent use of muscular and sexual forms also imbued his work with an explicit eroticism.

Santimamiñe inaugurated the next cycle of sculptures. The name of the work comes from the caves that burrow into mount Ereñuzar in Arteaga in the province of Biscay, with their galleries winding far into the underground distance.

Santimamiñe inaugurated the next cycle of sculptures. The name of the work comes from the caves that burrow into mount Ereñuzar in Arteaga in the province of Biscay, with their galleries winding far into the underground distance. Larrea saw a profound relation between the work and the spatial organization of the caves; he was also captivated by the anthropological and ancestral symbolism of the caves themselves, which boast paintings done by some of the earliest, prehistoric inhabitants of the region. Indeed, whether the works bear the names of local caves or not, and whatever the final configuration of the individual sculptures, a common feature of this series are the secret, labyrinthine paths to be travelled down, some of them for ever hidden from view, and which force space and spectator to be constantly on the move. Executed between 1970 and 1974, some of the finest works in the series are Santimamiñe I (1970-1971), Ferroviario (1971), Circe (1972), Trino (1973) and Santimamiñe II from 1974.

Larrea saw a profound relation between the work and the spatial organization of the caves; he was also captivated by the anthropological and ancestral symbolism of the caves themselves, which boast paintings done by some of the earliest, prehistoric inhabitants of the region. Indeed, whether the works bear the names of local caves or not, and whatever the final configuration of the individual sculptures, a common feature of this series are the secret, labyrinthine paths to be travelled down, some of them for ever hidden from view, and which force space and spectator to be constantly on the move. Executed between 1970 and 1974, some of the finest works in the series are Santimamiñe I (1970-1971), Ferroviario (1971), Circe (1972), Trino (1973) and Santimamiñe II from 1974.

In 1973, Larrea held his first retrospective exhibition at the municipal galleries in Durango. In the following year, he showed the Santimamiñe sculptures and other related works at the Galería Kreisler-2 in Madrid, where they were a great success with the critics. A further two exhibitions in 1975, one at the Galería Lúzaro in Bilbao, the other at the Galería Eder Arte in Vitoria, (featuring the previous works and others Larrea called Brocas) and a retrospective in the Ciudadela (Citadel) in Pamplona in 1977 marked the end of his individual exhibitions for some years. However, he continued exhibiting in group shows. In the 1970s, exhibitions of Basque art were a frequent phenomenon of the local artistic, political and festive scene and such shows were held all over the region. In view of its vigour and continuity, this may in fact be considered one of the most unusual and prolonged episodes of the diffusion and popular acclaim of the avant-garde plastic arts in modern times.

Larrea now began to concentrate on two developments. He produced both medium-sized sculptures cast in bronze and large public sculptures cast in iron, often developed from the bronze sculptures, rather as a painter bases a finished work on a preliminary sketch. They would be transferred to iron, to what the artist calls their “natural size”, more or less faithfully from the bronze original. The explicit concept behind the Brocas series first appeared in Larrea’s work in 1974 in a sculpture called Protobroca, although it is true that the vertical morphology had its precedents in Trino and Samotracia, not to mention some of his earlier geometric structures. But from here on, the vertical development would acquire the closed, straight form of the work tool (broca means bit) that gives its name to this series, as a sort of phallic instrument to penetrate space. Of the sculptures done in bronze, besides Protobroca, the most important are probably Broca Kenkenes and Broca, both from 1974. Broca Kenkenes from 1976 is one of the most interesting of the sculptures cast in iron, almost all of them public works, from the ten years after 1975; it originally stood in the grounds of Ajuria-Enea in Vitoria, now the residence and offices of the President of the Basque regional government, owned by the Museum of Alava and today in Artium, a relatively new museum of modern art in Vitoria. Also worthy of note are Abstracción 4, from 1979, produced for Lagun Aro in Mondragón, Abstracción 5, from 1982, commissioned by the Caja de Ahorros Vizcaína savings bank (today the Bilbao Bizkaia Kutxa or BBK) in the centre of Bilbao, another Brocafor the Caja Laboral Popular savings bank on Madrid’s Paseo de la Castellana (1983), surely one of the artist’s finest ever pieces, 1985’s Códice 4 for the University of Valladolid and the Venus de Santimamiñe 2, from 1985-1986 and today in the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum.

Larrea now began to concentrate on two developments. He produced both medium-sized sculptures cast in bronze and large public sculptures cast in iron, often developed from the bronze sculptures, rather as a painter bases a finished work on a preliminary sketch. They would be transferred to iron, to what the artist calls their “natural size”, more or less faithfully from the bronze original. The explicit concept behind the Brocas series first appeared in Larrea’s work in 1974 in a sculpture called Protobroca, although it is true that the vertical morphology had its precedents in Trino and Samotracia, not to mention some of his earlier geometric structures. But from here on, the vertical development would acquire the closed, straight form of the work tool (broca means bit) that gives its name to this series, as a sort of phallic instrument to penetrate space. Of the sculptures done in bronze, besides Protobroca, the most important are probably Broca Kenkenes and Broca, both from 1974. Broca Kenkenes from 1976 is one of the most interesting of the sculptures cast in iron, almost all of them public works, from the ten years after 1975; it originally stood in the grounds of Ajuria-Enea in Vitoria, now the residence and offices of the President of the Basque regional government, owned by the Museum of Alava and today in Artium, a relatively new museum of modern art in Vitoria. Also worthy of note are Abstracción 4, from 1979, produced for Lagun Aro in Mondragón, Abstracción 5, from 1982, commissioned by the Caja de Ahorros Vizcaína savings bank (today the Bilbao Bizkaia Kutxa or BBK) in the centre of Bilbao, another Brocafor the Caja Laboral Popular savings bank on Madrid’s Paseo de la Castellana (1983), surely one of the artist’s finest ever pieces, 1985’s Códice 4 for the University of Valladolid and the Venus de Santimamiñe 2, from 1985-1986 and today in the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum.

A major feature of Larrea’s work in the late 1970s and ‘80s was his treatment of the surface or epidermis of his sculptures. He was becoming increasingly interested in modelling and in the potential of polychrome. Although the only precedents in his work were the two Cepa, in 1979 he was prompted to make a sculpture, Mikela, and in 1983 a relief, Duccio, in polyester with lacquer paints on a gilt ground and polychrome, his acknowledgement of the techniques used by the old mediaeval and Renaissance guilds and a harking back to his own apprenticeship. Produced after a visit to Italy, Duccio may be considered a tribute to Sienna Gothic, as its title suggests, while Mikela is more of a tribute to Spanish imagery. The interest in providing his sculptures with a colour different from the original material is also appreciablein his large works in iron. Códice 4 was the first to be given the pictorial treatment, albeit with industrial paints. Until then his large irons had kept, more or less stabilized, the colour of the oxidised material used in their creation.

A major feature of Larrea’s work in the late 1970s and ‘80s was his treatment of the surface or epidermis of his sculptures. He was becoming increasingly interested in modelling and in the potential of polychrome. Although the only precedents in his work were the two Cepa, in 1979 he was prompted to make a sculpture, Mikela, and in 1983 a relief, Duccio, in polyester with lacquer paints on a gilt ground and polychrome, his acknowledgement of the techniques used by the old mediaeval and Renaissance guilds and a harking back to his own apprenticeship. Produced after a visit to Italy, Duccio may be considered a tribute to Sienna Gothic, as its title suggests, while Mikela is more of a tribute to Spanish imagery. The interest in providing his sculptures with a colour different from the original material is also appreciablein his large works in iron. Códice 4 was the first to be given the pictorial treatment, albeit with industrial paints. Until then his large irons had kept, more or less stabilized, the colour of the oxidised material used in their creation.

In 1983, at the invitation of the Basque regional government, Larrea took several works to the International Chicago Art Fair, once again in the company of fellow artists Basterretxea and Mendiburu.

Another major change came in the late 1980s (in 1987 to be precise), with the appearance of figurative sculptures, a series of human images initiated with the head of Gattamelata, the Condottiere portrayed on horseback by Donatello. 1987 marked the 500th anniversary of Donatello’s death and Larrea produced the head in that year in homage to the Italian sculptor. A number of other heads followed: Profeta, Pastor, several Senador, from the same year, as well as full body-length sculptures, including Virgen, from 1989, for the parish church of Rosario in Bilbao, and the Ángel, from the same year, for the cemetery at Zumárraga in the province of Guipúzcoa, the complexity, size and expressive ambition of which marks it out as the high point of this phase. From here on, he happily alternated figurative and abstract sculptures and major abstract works like the Retablo de la libertad, (1990) appeared more or less alongside almost figurative works like Torso 2, 3 and 4, the first two from 1994 and the third from 1995, Agamenón (1995), Hombre de Gernika (1999), a tormented human body fallen to the ground,  Dodekathlos (1997-98) and a large head of one-time Biscay Provincial Council chief executive Makua, from 2003, now sited in Bilbao’s new Miribilla district. This series of figurative works also shed light on the anthropomorphic nature of those abstract sculptures recalling the upright figure of a man

Dodekathlos (1997-98) and a large head of one-time Biscay Provincial Council chief executive Makua, from 2003, now sited in Bilbao’s new Miribilla district. This series of figurative works also shed light on the anthropomorphic nature of those abstract sculptures recalling the upright figure of a man and which to a greater or lesser extent certainly evoked the human form. The muscular forms of human torsos have always been a part of the modelling of Larrea’s works. Sculptures that describe surroundings like caves and labyrinths, whether habitable or not, are in fact full of human references, however fragmentary: they look to us like rooms that have been acted upon, visited and explored by man. Similarly, the more or less anthropomorphic, hollow figures conjure up images of man dramatically inhabiting himself, exploring himself in his drift towards an impenetrable intimacy.

and which to a greater or lesser extent certainly evoked the human form. The muscular forms of human torsos have always been a part of the modelling of Larrea’s works. Sculptures that describe surroundings like caves and labyrinths, whether habitable or not, are in fact full of human references, however fragmentary: they look to us like rooms that have been acted upon, visited and explored by man. Similarly, the more or less anthropomorphic, hollow figures conjure up images of man dramatically inhabiting himself, exploring himself in his drift towards an impenetrable intimacy.

In 1994, Larrea staged a major retrospective in the Sala Rekalde gallery in Bilbao, which was followed in 1996 by an exhibition of his latest work at the city’s Galería A+T.

Another characteristic that imposed itself on Larrea’s work at this time that affected both the epidermis and the structure of the body is appreciable in Retablo de la libertad, a major work cast in bronze and remarkable for its size and vortex-like composition. The characteristic in question is a definite tendency towards dematerialization. Although the tendency had appeared in works previous to Retablo, it is intensified here both by the sheer size of the work and the material it is made from, Retablo being Larrea’s first public work to be done in bronze rather than iron and the source of some major technical headaches for the artist.

Another characteristic that imposed itself on Larrea’s work at this time that affected both the epidermis and the structure of the body is appreciable in Retablo de la libertad, a major work cast in bronze and remarkable for its size and vortex-like composition. The characteristic in question is a definite tendency towards dematerialization. Although the tendency had appeared in works previous to Retablo, it is intensified here both by the sheer size of the work and the material it is made from, Retablo being Larrea’s first public work to be done in bronze rather than iron and the source of some major technical headaches for the artist.  Sited in an architectural development in Lejona, just outside Bilbao, this high relief bears the signs of Larrea’s interest in modelling in small planes that are sharper and edgier than in the previous bronzes, with a more direct imprint, and in reducing the proportional thickness of the sheet or plate that makes up the sculpture, thus facilitating a more complex, nervous movement. This was eventually to lead to the replacement of full forms, down which the light pours smoothly and uninterruptedly, by vibrant surfaces in which shadow and reflections take on a more painterly, Impressionist look, the whole appearing more unreal, more abrupt, leaner. This loss of mass is not just apparent, as the Makila series makes clear (the series is a symbolic representation of and homage to shepherding that transforms the traditional shepherd’s makila or stick into a slim vertical sculpture); from the earliest approaches to the theme, Makila 1 and 2, from 1985 to 1987, to the versión definitiva en hierro coloreado de 1996, the work contracts and twists to become a virtually linear body in which the convex forms are so faceted that they do not interrupt the rapid continuity of the upward rhythm.

Sited in an architectural development in Lejona, just outside Bilbao, this high relief bears the signs of Larrea’s interest in modelling in small planes that are sharper and edgier than in the previous bronzes, with a more direct imprint, and in reducing the proportional thickness of the sheet or plate that makes up the sculpture, thus facilitating a more complex, nervous movement. This was eventually to lead to the replacement of full forms, down which the light pours smoothly and uninterruptedly, by vibrant surfaces in which shadow and reflections take on a more painterly, Impressionist look, the whole appearing more unreal, more abrupt, leaner. This loss of mass is not just apparent, as the Makila series makes clear (the series is a symbolic representation of and homage to shepherding that transforms the traditional shepherd’s makila or stick into a slim vertical sculpture); from the earliest approaches to the theme, Makila 1 and 2, from 1985 to 1987, to the versión definitiva en hierro coloreado de 1996, the work contracts and twists to become a virtually linear body in which the convex forms are so faceted that they do not interrupt the rapid continuity of the upward rhythm.

A new feature making its appearance in this work are the straight, architectural, geometric lines integrated in the organic forms that had been exclusive to Larrea’s work since Samotracia in 1970-1971: These lines create the kind of tension between antagonistic parts not seen since the Cárceles from 1969-1971. However, the aggressive enveloping relationship that was the principal argument of the earlier pieces is missing from the later works; here the interest lies in imbuing the sculpture with an evident architectural organization, ultimately deriving from the artist’s own interest in architecture itself. Zumárraga from 1989 was the first work to which such elements were added. They were subsequently seen in Torso antorcha (1994), 1995’s

here the interest lies in imbuing the sculpture with an evident architectural organization, ultimately deriving from the artist’s own interest in architecture itself. Zumárraga from 1989 was the first work to which such elements were added. They were subsequently seen in Torso antorcha (1994), 1995’s  Agamenón, where they provide the elongated support for the subject’s head, Alas from 1996, a sculpture sited at the edge of a main road in Zumárraga, in which, in a similar fashion, wings (the alas of the title) top off a cylindrical column, Algorta (2002) and Arrigorriaga, also from 2002. Abstracción 4 from 1979, sited in Mondragón could be held up as a precedent, although the geometric component there was not actually part of the sculpture, being provided by the architecture of the building itself, up which the organic body “climbs” (an option he used again in Amezola a sculpture from 2005, sited in the Bilbao railway station of the same name), but the intention and the result may well seem not dissimilar.

Agamenón, where they provide the elongated support for the subject’s head, Alas from 1996, a sculpture sited at the edge of a main road in Zumárraga, in which, in a similar fashion, wings (the alas of the title) top off a cylindrical column, Algorta (2002) and Arrigorriaga, also from 2002. Abstracción 4 from 1979, sited in Mondragón could be held up as a precedent, although the geometric component there was not actually part of the sculpture, being provided by the architecture of the building itself, up which the organic body “climbs” (an option he used again in Amezola a sculpture from 2005, sited in the Bilbao railway station of the same name), but the intention and the result may well seem not dissimilar.

Without ever straying from the essential naturalism of his sculpture, from the use of forms and the spatial behaviour of natural organisms, as he developed and matured Larrea tried to add distancing, “artificial” effects, as a means of stimulating the spectator into thinking about the primordial nature of his objects and as a source of conflict and tension, of drama and unease. And while from his earliest works the artist has clearly shown his interest in establishing his aesthetic preferences and the references he signals for his works and in making them manifest through his configurations or titles, in recent years he has inclined increasingly towards classical Greek and Roman culture, Hellenism in particular: we need only look back to his early work Samotracia,  which he has paid tribute to frequently through his formal options and artistic genres: the Torsos in general,

which he has paid tribute to frequently through his formal options and artistic genres: the Torsos in general, his Torso capitel (1996), the set of three Columnas, from 2006 to 2007, forcefully suggesting the remains of a temple, and his literary or mythological characters and episodes, including Agamenón, Torso 4, created as an homage to Ajax, Dodekathlos and Esculapio (2011). In paying homage to architecture and its references to classicism, its monumental presence and the textual clarity involved in the appearance of column capitals, shafts and bases, and given the fact that a number of features anticipated in previous years appear in it, Columnas is a very significant work, summing up several of Larrea’s major lines of exploration of the previous decade. Dodekathlos, one of the most ambitious works in cast iron, stands outside the city of Bilbao’s Euskalduna Conference & Performing Arts Centre as a tribute to the workers of the old shipyards that used to stand on the site of the present building.

his Torso capitel (1996), the set of three Columnas, from 2006 to 2007, forcefully suggesting the remains of a temple, and his literary or mythological characters and episodes, including Agamenón, Torso 4, created as an homage to Ajax, Dodekathlos and Esculapio (2011). In paying homage to architecture and its references to classicism, its monumental presence and the textual clarity involved in the appearance of column capitals, shafts and bases, and given the fact that a number of features anticipated in previous years appear in it, Columnas is a very significant work, summing up several of Larrea’s major lines of exploration of the previous decade. Dodekathlos, one of the most ambitious works in cast iron, stands outside the city of Bilbao’s Euskalduna Conference & Performing Arts Centre as a tribute to the workers of the old shipyards that used to stand on the site of the present building.

Meanwhile, Larrea has continued to progress in bronze casting, something we can appreciate in Retablo de la libertad, Makua, the three sculptures from 2005 sited in the Plaza de San José in Bilbao in homage to the architects and engineers who helped to build the new Bilbao in the 19th and early 20th centuries, men like Churruca; Hoffmeyer, Alzola and Achúcarro; Bastida, the Columnas mentioned above and Manos Fuente (2010) for a cemetery in Arrigorriaga, not far from Bilbao. But the most significant example of his growing mastery of bronze is surely Esculapio, which he has executed for the interior of the IMQ private medical organization’s new building on Zorrozaure wharf in Bilbao.

Meanwhile, Larrea has continued to progress in bronze casting, something we can appreciate in Retablo de la libertad, Makua, the three sculptures from 2005 sited in the Plaza de San José in Bilbao in homage to the architects and engineers who helped to build the new Bilbao in the 19th and early 20th centuries, men like Churruca; Hoffmeyer, Alzola and Achúcarro; Bastida, the Columnas mentioned above and Manos Fuente (2010) for a cemetery in Arrigorriaga, not far from Bilbao. But the most significant example of his growing mastery of bronze is surely Esculapio, which he has executed for the interior of the IMQ private medical organization’s new building on Zorrozaure wharf in Bilbao. The sculpture, also called El cortejo de las serpientes, as it portrays the serpents that symbolically accompany Aesculapius, the ancient god of medicine, is formed by two long vertical bodies that are entwined about the staff of Aesculapius, with their heads facing each other at the top. The unusual height for a work cast in bronze, together with the robust thickness of the plate featured, makes it a genuine technical challenge. Though similar to the dematerialization found in Makila, what we encounter in the new work is a greater fluidity of composition: the bronze surfaces are given increased continuity, the cuts follow the upward lines and there are no bulky protuberances, which means it flows uninterruptedly. All in all, the modelling oozes sensuality, leading to a new and more harmonious image.

The sculpture, also called El cortejo de las serpientes, as it portrays the serpents that symbolically accompany Aesculapius, the ancient god of medicine, is formed by two long vertical bodies that are entwined about the staff of Aesculapius, with their heads facing each other at the top. The unusual height for a work cast in bronze, together with the robust thickness of the plate featured, makes it a genuine technical challenge. Though similar to the dematerialization found in Makila, what we encounter in the new work is a greater fluidity of composition: the bronze surfaces are given increased continuity, the cuts follow the upward lines and there are no bulky protuberances, which means it flows uninterruptedly. All in all, the modelling oozes sensuality, leading to a new and more harmonious image.

Javier Viar